Medieval Dublin – alive, alive oh!

A report from the tenth annual symposium of the Friends of Medieval Dublin, held at Trinity College, Dublin, on Saturday, 24 May 2008.

Dr Peter Crooks

This autumn marks the thirtieth anniversary of the famous ‘Viking march’ organized by Professor F.X. Martin and the Friends of Medieval Dublin (FMD) as part of the campaign for the preservation of the incomparable archaeological treasures at Wood Quay. Some twenty thousand people marched on Leinster House that September day in 1978. FMD was then a fledgling group, established in 1976 to ‘foster by every available means an appreciation of the medieval Dublin heritage’ – in the words of ‘F.X.’ himself. Passions sometimes wane or run to despondency when the moment of immediate crisis passes. From the remove of three decades, however, it is clear that FMD has been enormously successful in harnessing that initial enthusiasm and in maintaining long-term public awareness of and academic interest in Dublin’s past. This was apparent when FMD recently convened its tenth annual symposium at Trinity College, Dublin.

The FMD symposium began life in 1999 as a vehicle designed primarily for the dissemination of findings from an upsurge of archaeological activity in the heart of Dublin, but it rapidly became an annual showcase for cutting-edge scholarship on almost every aspect of the archaeology, history, and literary and material culture of the medieval city and county. From the first, speakers undertook to publish their papers in the new Medieval Dublin series, edited by the current chairman of FMD, Dr Seán Duffy, and published by Four Courts Press with financial assistance from a more enlightened Dublin Corporation. Since 2000, seven volumes have appeared, containing a grand total of sixty-eight original articles, and the proceedings of the eighth and ninth symposia are already in the press. Taken together, this represents a remarkable effusion of scholarship.

Little wonder, then, that when the tenth installment got underway at 9.30 a.m. on Saturday, 24 May 2008, a large Trinity lecture theatre was already nearing capacity and latecomers found themselves perching on the sidelines in the hope of finding a seat. This year’s symposium was notable for the breadth of its chronological, geographical and thematic coverage.

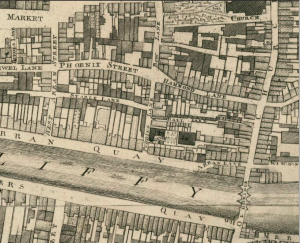

The prevailing image conjured up by medieval Dublin is of the Viking settlement established on the south side of the Liffey, but archaeologists have long known of the riches to be found beyond the old city walls. Sinéad Phelan opened proceedings with a report on the evidence for Hiberno-Norse activity on Hammond Lane near St Michan’s church, just across the medieval bridge (now the site of Fr Mathew Bridge) that linked the walled city to the ‘transpontine suburb’ on the Liffey’s northern bank.

Alan Hayden’s paper brought listeners across the medieval bridge again to the south side, as he relayed his findings from a sodden dig in the alluvial deposits of ‘disgusting’ (that is, St Augustine’s) street. Dublin’s archaeologists, so it seems, find punning irresistible:

Stephen Harrison’s paper (‘Bride Street revisited’) took a fresh look at a furnished Viking grave discovered in Bride Street in the nineteenth century. The artifacts were miscatalogued by antiquarians and, consequently, misinterpreted. With some resourceful jigsaw work, Harrison convincingly pieced together three sections of the Viking sword placed in the original grave. From this, he argued on stylistic grounds that the grave was relatively late in date, suggesting that the Bride Street inhumation was a self-conscious, even ostentatious, revival of the practice of pagan furnished burial at a time (the 10th century) when such a ritual was becoming increasingly rare.

Other papers ranged into the suburbs and county of Dublin. Kevin Lohan’s dig on the site of Clancy barracks, Islandbridge, uncovered a very early wooden revetment on what was then the Liffey bank, certainly pre-Viking and perhaps even Iron Age in date.

Meanwhile, Ed O’Donovan’s excavation at St Nahi’s church in Dundrum (on a hill near the new Luas bridge) revealed a series of fortified enclosures around the former monastic foundation. This caused him to make the intriguing suggestion that the dún (fort) of Dún Droma (the fort of the ridge) is perhaps not, as is popularly supposed, Dundrum Castle – which stands on a ridge overlooking that new cathedral to consumerism, Dundrum Town Centre – but rather the much earlier hill-side fortification at St Nahi’s.

Meanwhile, Ed O’Donovan’s excavation at St Nahi’s church in Dundrum (on a hill near the new Luas bridge) revealed a series of fortified enclosures around the former monastic foundation. This caused him to make the intriguing suggestion that the dún (fort) of Dún Droma (the fort of the ridge) is perhaps not, as is popularly supposed, Dundrum Castle – which stands on a ridge overlooking that new cathedral to consumerism, Dundrum Town Centre – but rather the much earlier hill-side fortification at St Nahi’s.

Historical perspectives on the medieval city and county were provided by two promising scholars from TCD. Áine Foley’s work on the social history of the royal manors of medieval Dublin (Crumlin, Esker, Saggart and Newcastle Lyons) has led her to investigate the incidence of crime in Ireland at opening of the fourteenth century. Disorder in this period is often attributed to the ‘degeneracy’ of the English colonists – the process by which the descendants of the first Anglo-Norman invaders of Ireland departed from English social and cultural mores. Foley argued, however, that crime was very much part of the social landscape of early fourteenth-century England and that, in this respect, the nefarious deeds of English tenants on Dublin’s royal manors were not ‘degenerate’ but rather of a kind with the criminal behaviour of their English cousins across the Irish Sea.

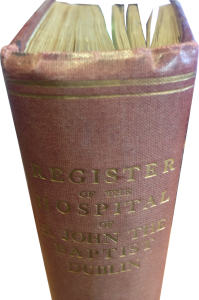

Grace O’Keeffe, also of TCD, presented an exciting prospectus of her research on the Augustinian hospital of St John the Baptist, which was situated ‘without the New Gate’ of the medieval city, off St Thomas’ Street. O’Keeffe’s work on the register of the hospital – a collection of land grants and related documents – served almost as a call to arms, as she suggested a research agenda that could occupy scholars for some decades, namely an intensive analysis of the thousands of citizens named in the surviving charters of religious foundations in and around medieval Dublin. Such a project would enormously enhance our understanding of the social structure of the medieval city, and in particular of the élite group of citizens that controlled the governance of the municipality.

Grace O’Keeffe, also of TCD, presented an exciting prospectus of her research on the Augustinian hospital of St John the Baptist, which was situated ‘without the New Gate’ of the medieval city, off St Thomas’ Street. O’Keeffe’s work on the register of the hospital – a collection of land grants and related documents – served almost as a call to arms, as she suggested a research agenda that could occupy scholars for some decades, namely an intensive analysis of the thousands of citizens named in the surviving charters of religious foundations in and around medieval Dublin. Such a project would enormously enhance our understanding of the social structure of the medieval city, and in particular of the élite group of citizens that controlled the governance of the municipality.

The proceedings closed with a presentation of a different kind from Triona Nicholl. Nicholl is a member of the crew of the Sea Stallion, a reconstruction of the Viking warship known as ‘Skuldelev 2’ that was discovered in Roskilda fjord, Denmark, and which has been shown to have been built from Irish oak felled c.1042 near Dublin. She treated the symposium to a gritty behind-the-scenes account of life on board the Sea Stallion during her ‘homecoming’ voyage from Denmark to Dublin in July and August 2007, including everything from the cramped sleeping accommodation and the 80 cm2 luggage allocation to the ‘bucket-and-chuck-it’ toilet facilities. On 19 June 2008, when the Sea Stallion sets sail from Dublin on its return journey, Nicholl will be manning her oars once again.

The proceedings closed with a presentation of a different kind from Triona Nicholl. Nicholl is a member of the crew of the Sea Stallion, a reconstruction of the Viking warship known as ‘Skuldelev 2’ that was discovered in Roskilda fjord, Denmark, and which has been shown to have been built from Irish oak felled c.1042 near Dublin. She treated the symposium to a gritty behind-the-scenes account of life on board the Sea Stallion during her ‘homecoming’ voyage from Denmark to Dublin in July and August 2007, including everything from the cramped sleeping accommodation and the 80 cm2 luggage allocation to the ‘bucket-and-chuck-it’ toilet facilities. On 19 June 2008, when the Sea Stallion sets sail from Dublin on its return journey, Nicholl will be manning her oars once again.

Readers can look forward to the proceedings of the symposium appearing in print during 2009 as Medieval Dublin X. And, if F.X. Martin attended the symposium in spirit, he must surely have been gratified to see that, thirty years on, scholarship on medieval Dublin is not just alive, but kicking.